Charter Research Aims to Improve Diversity in Alzheimer’s Trials

Scientists know that some drugs work differently depending on a person’s ethnic background. Yet the participants of clinical trials often don’t reflect the diversity within the population. While 14 percent of Americans are Black and 18 percent Hispanic, they account for less than 6 percent of clinical trial participants.

Small genetic differences change the way that some medicines are broken down, absorbed, and distributed through the body. There are important differences between men and women, and across different ethnic backgrounds that alter the effectiveness of a drug. According to experts, increasing the participation of minorities in clinical trials will also ensure the development of better, personalized treatments.

When it comes to Alzheimer’s disease, Black and Hispanic people are at a higher risk of developing the disease than white people. In Black people, the risk is almost twice as high, while in Hispanic people the risk is increased almost one and a half times. Yet, they are often diagnosed at later stages than white people.

“People from different ethnic backgrounds experience the same symptoms,” said Jeff Pohlig, CEO of Charter Research. “But people in minority populations are less inclined to visit their doctor.” So not only is there a race-based discrepancy in risk of developing Alzheimer’s — there is also a difference in likelihood to seek treatment.

“We know that particularly the Hispanic populations are less likely to seek treatment for memory loss, confusion, or other cognitive problems,” Pohlig said. “Inclusion in clinical trials may be a step toward getting more involvement from the outset. As we develop new treatments that may gain FDA approval, that will help facilitate people being comfortable with reaching out for that type of help.”

In the interest of achieving greater equity in access to brain health care, researchers and pharmaceutical companies are taking active steps to increase diversity in clinical trials. One study, known as the Bio-Hermes study and run by the Global Alzheimer’s Platform Foundation (GAP), is tailoring its recruitment to ensure that 20 percent of participants are minorities. Pohlig explains why this poses a challenge: “Black and Hispanic people are sometimes hesitant to participate due to historical distrust in the medical establishment, and most trial sites haven’t made a good attempt at connecting with minorities.”

But, he said, Charter Research is working to address these issues and recruit more diverse participants. “We produce consent forms and other required study forms in both English and Spanish,” Pohlig explains. “We administer memory tests in Spanish.” In addition to developing study materials in Spanish, Charter Research also hires Spanish-speaking staff at its Winter Park location.

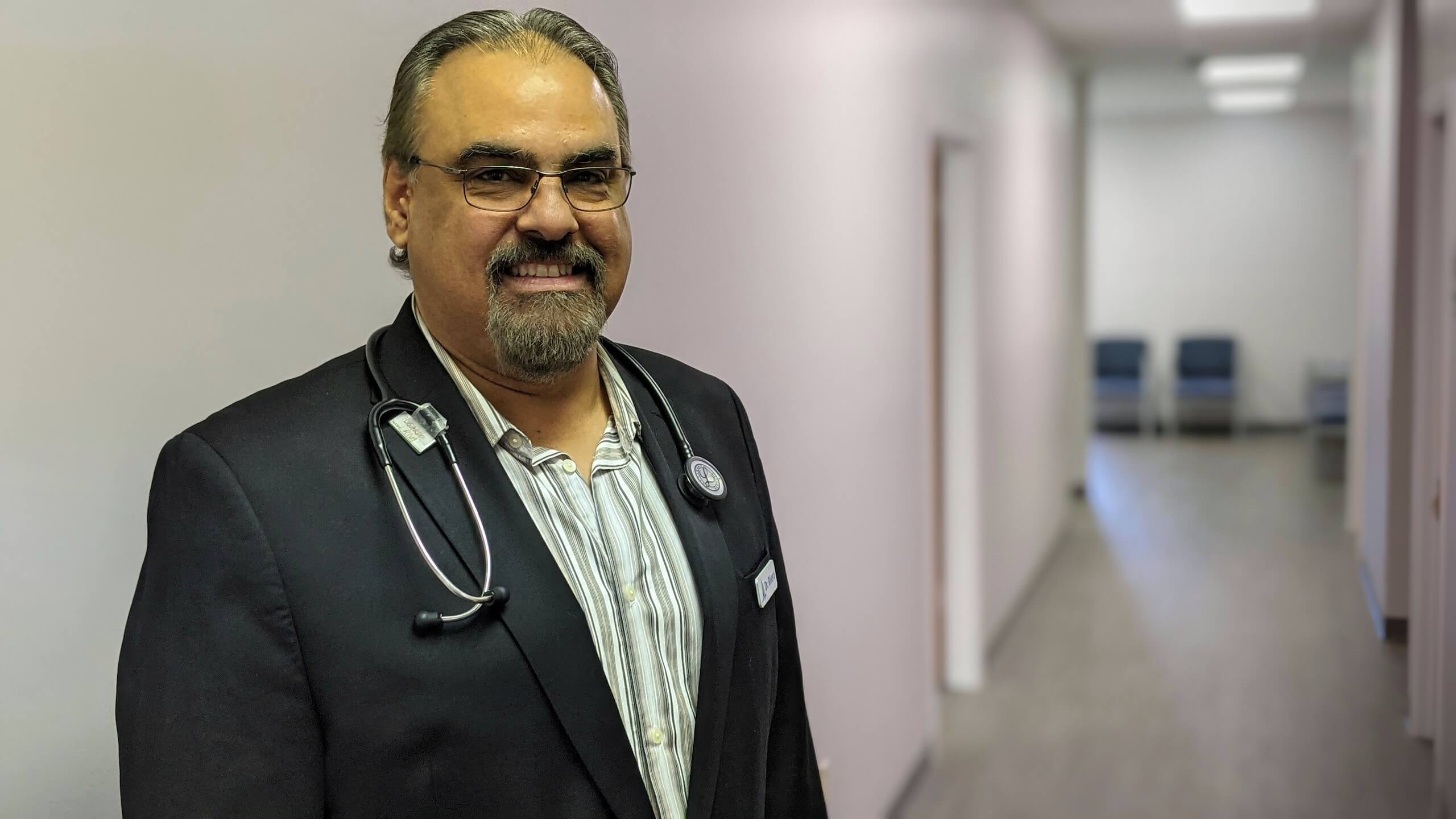

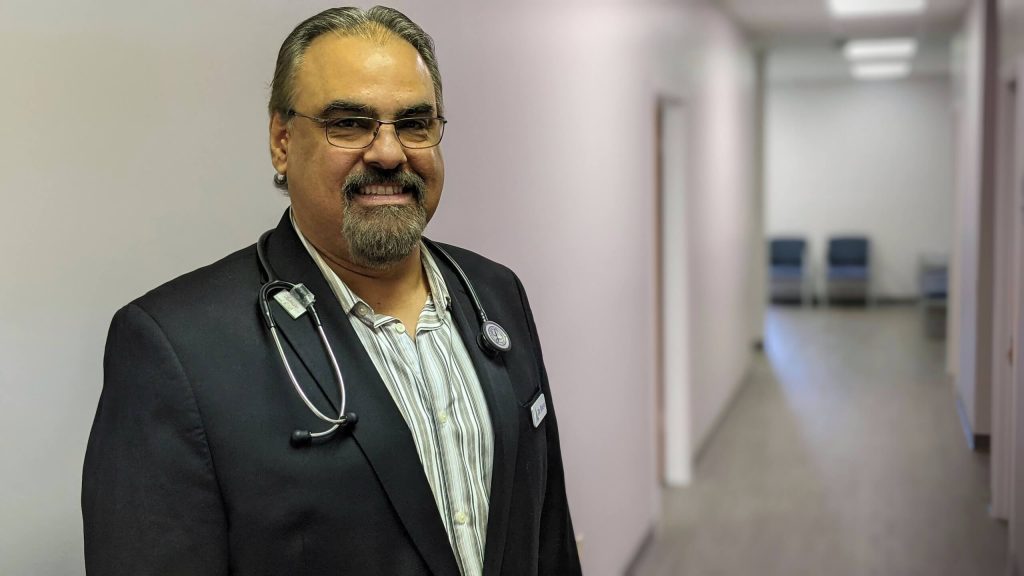

Dr. Edgardo Rivera, Principal Investigator at Charter Research’s Winter Park research center, said ensuring that staff is diverse goes a long way toward fostering diversity in trials.

“People feel listened to and more comfortable when they can speak the same language as their doctor,” Rivera said. “It helps especially in the Hispanic community, where multiple members of the extended family are involved in the decision-making process. Speaking the same language helps break the stigma of Alzheimer’s and build trust with the participant and their family.”

This isn’t just anecdotal: Research has found that a person’s trust in their healthcare provider is closely tied to patient and care provider being of the same race and/or ethnicity.

Historically, people from minority groups have represented fewer than 5 percent of participants in clinical trials. That’s why the Charter Research team is focused on improving inclusion.

“We’re working to try to change that,” Pohlig said. “We want to be testing new potential medications and innovative new therapies in the people who will be receiving them. It’s important from a scientific and equity standpoint.”